FreeBSD: The Path Not Taken, and Why It Matters

Every so often, a question bubbles up in the tech community: “Why doesn’t FreeBSD have [insert popular Linux feature here]?” Lately, the subject is often Flatpak, a containerized application distribution system that has gained significant traction in the Linux desktop world. As Linux desktops increasingly lean on such solutions to solve the distribution fragmentation problem, users accustomed to this paradigm look at FreeBSD and wonder why it isn’t following suit, seemingly lagging behind in modern software distribution.

The answer, it turns out, reveals the very soul of FreeBSD, a philosophy deeply rooted in its Unix heritage.

Solving a Problem That Doesn’t Exist Here: The FreeBSD Perspective

A recent forum discussion on this very topic illuminated the core difference. A user pointed out that Flatpak is a brilliant solution to a uniquely Linux problem. In the vast and diverse Linux ecosystem, with countless distributions, each with its own set of libraries, package managers, and update cycles, delivering a single application that “just works” everywhere is a monumental challenge. Flatpak and Snap are clever, albeit complex, layers built to abstract away that fragmentation, providing a consistent runtime environment across disparate systems.

FreeBSD, on the other hand, fundamentally doesn’t suffer from this problem. As one insightful developer in the discussion succinctly noted, “we have pkg and ports that cater to FreeBSD.” The operating system is a single, cohesive entity, meticulously maintained and developed by a centralized project. The base system (the kernel and core utilities) and the vast collection of third-party applications managed by the Ports Collection are developed and tested in concert. There is one primary target, one consistent way of doing things. The inherent design of FreeBSD negates the need for a universal, cross-distribution wrapper like Flatpak; the problem it solves simply doesn’t exist within the FreeBSD paradigm.

The Allure of a Cohesive System: Predictability and Reliability

This isn’t merely about package management; it’s a profound, fundamental difference in philosophical approach. Linux, at its heart, is a kernel, around which a sprawling constellation of independent distributions has formed, each with its own vision and implementation. FreeBSD, by contrast, is a complete, integrated operating system, where the kernel, userland utilities, and even the documentation are developed as a single, unified project. This deep integration is its superpower, fostering a level of internal consistency that is rare in the open-source world.

This integrated approach provides an unparalleled level of predictability and stability that can feel foreign to those accustomed to the often-chaotic Linux world. The FreeBSD Handbook, a comprehensive and meticulously maintained resource, is legendary for a reason—it documents a system that is remarkably consistent and coherent across all its components. You don’t need to hunt down a different wiki, forum, or set of instructions for every minor variation or flavor of the OS; the core principles and functionalities remain consistent, simplifying administration and troubleshooting significantly.

Jails: The Original Container and a Deeper Isolation

When the conversation inevitably turns to security and sandboxing—a key selling point of modern container technologies like Flatpak—FreeBSD veterans will invariably point to Jails. Jails are a powerful, kernel-level sandboxing mechanism that has existed for over two decades, predating many contemporary container solutions. They are, in many ways, arguably the conceptual inspiration for much of modern container technology.

With Jails, you can create isolated environments with their own filesystems, users, processes, and even dedicated network stacks (via VNET Jails). This provides a robust and flexible system for security and service separation, built directly into the very fabric of the OS. Unlike user-space sandboxing layers, Jails offer a deeper, more fundamental level of isolation, making them an incredibly effective tool for hosting multiple services or applications on a single machine while maintaining strong security boundaries. From a security perspective, it’s often considered a more fundamental and less abstract solution than many user-space containerization approaches.

A Different Kind of Power: Stability Over Trend-Chasing

So, will FreeBSD ever embrace Flatpak or similar technologies? The prevailing sentiment within the FreeBSD community is often a resounding “God, I hope not!” This isn’t born out of arrogance or a resistance to innovation. Rather, it stems from a deep understanding that adopting such a solution would mean importing a complex layer designed to solve a problem that FreeBSD, by its very design, does not have. It would introduce unnecessary complexity and potentially compromise the very coherence that makes FreeBSD unique.

FreeBSD represents a different philosophy: one of deliberate, careful integration, stability, and long-term consistency over rapid, fragmented innovation and chasing every new trend. It’s a trade-off. While you might not always have the absolute latest bleeding-edge application packaging format, you gain a system of unparalleled coherence, stability, and security. In an industry often obsessed with chasing the newest, flashiest technologies, there’s a quiet, enduring power in the path not taken—a power derived from a commitment to foundational principles and a holistic system design.

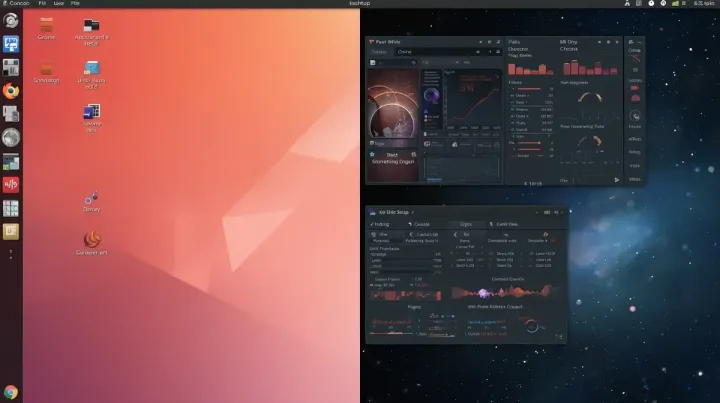

This commitment ensures that FreeBSD remains a reliable, predictable, and secure choice for critical infrastructure, servers, and even specialized desktop environments where stability and control are paramount. It’s a testament to the idea that sometimes, the best way forward is to stay true to a well-defined, robust architectural vision, rather than simply adopting solutions designed for different problems.